Leading Face-to-Face vs Remotely is NOT Just a Technology Issue

With what going on today with many people being forced into virtual/remote work, it is important for leaders to know that keeping team connection viable and relevant requires special attention. Two qualitative global studies of virtual project teams found that individuals in virtual situations perform differently than face-to-face teams in many instances (Brown, Duck, & Jimmieson, 2014; Morgan, Paucar-Caceres, & Wright, 2014).

How we connect in virtual/remote work affects how we communicate and how we communicate can determine how trusting we are of each other which affects our relationships and connection to each other. Herein lies the challenge leaders when leading face-to-face versus remotely. Keeping connections and relationships in the ideal states requires understanding how we connect and relate as a team remotely.

Relationships are based on a common connection we feel toward each other giving us a sense of belonging as part of a tribe. Whether small and intimate, a larger representative group, a division, a company, or an industry of people, tribes come together for a common purpose. High performance teams working through technology are akin to tribes and as such have all the same psychological, psychosocial, and behavioural idiosyncrasies of any other collections of human beings.

The description of “tribe” instead of team is purposeful as a tribe is a collective of unique individuals that each have a role and purpose to achieve a common goal while maintaining strong relational bonds of safety, connection, social interaction, and purpose.

Team leaders are representative chieftains that express and emulate the values, efficacy, purpose and direction of the tribe. These team chieftains continually emulate and guide psychosocially how the team collectively fits into the greater network of organization, humans, and environment within which they interact. The primary focus of a team leader is to explain the team’s purpose and how it contributes to the wider vision of the organisation.

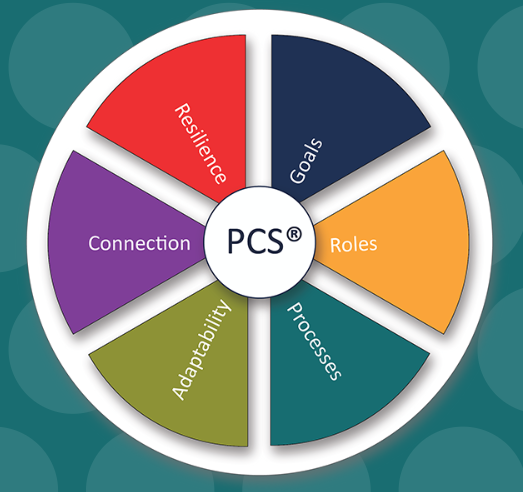

Strong team leadership comes in the form of goal and role setting, process completion and the ability to direct, coach, support and/or delegate members of the tribe based on the individual’s needs. As such, and as the leader of any tribe, it is up to the team leader to influence the psychological and psychosocial connection of the tribe, so they come together as individual, meaningful parts of the greater whole.

Effective high-performance team leaders guide their tribe through transactional and transformational development to develop focus, strong connections, relationship orientation, and highly functional tribes with operative communication and high team trust.

To be successful managing virtual employees requires knowing the effects of behavioral responses that contribute to social communication practices, organizational outcomes, and hindrances to building interpersonal trust, Politis (2014). Individual behavioural variances were shown) to influence trust in organizational relationships (Avolio, Sosik, Kahai, & Bake, 2014). Therefore, knowing your teams individually and working on situational leadership based on the comfort level of the individual is key. Just because someone works a certain way in face-to-face, they may be better or more uncomfortable in remote work. The only way to know this is by keeping an open dialogue.

The most important criteria for successful virtual/remote work output are trust, communication, collaboration, understanding geographical and cultural differences and knowing these characteristics are influenced by employee behavior and job strain (Lockwood, 2015; Petković, Orelj, & Lukić, 2014). Being trusting is the most important quality of virtual work; not being trustworthy can result in a negative work environment which in turn may influence job strain for the virtual workgroup and individual (Guinalíu & Jordán, 2016; Jiang & Probst, 2015).

Trust is a cornerstone of developing connections and a lasting relationship. The key influencers to trust are good communication, accountability and reliability. When the team or team members communicate with each other the interaction is clear and relevant and each person understands the takeaway or purpose of the discussion. During the decision, people take control and responsibility for their role in the smaller task at hand which could have a specific outcome that is measurable, with an achievable task that is relevant to the overall goals and the person’s particular role, with a specific time frame.

Different from traditional shared office space work environments, virtual distance situations have been shown to increase stress due to amplified difficulties in communicating through technology, decision processes that are often ambiguous, the lack of social interaction, and the lack of trust-building (Johns & Gratton, 2013; Judge & Zapata, 2015).

Short (2014) demonstrated that the lack of face-to-face interaction for virtual/remote work reduced trust and has a negative effect on employee social behaviour. Even when technology is at the highest standards, Lockwood (2016) demonstrated that good communication is hindered by technology, leadership, meeting skills, and even language and culture issues effecting employee behavior in virtual work.

Team leaders may need to make accommodations to communication styles and frequencies, goal setting or roles, or process based on the evolving issues that are inevitable especially in times of crisis, such that we have with the coronavirus. These accommodations can take the form of restructuring work, processes, or procedures, as well as creating more participative, more open, communicative, and trusting virtual situations (Hoch & Kozlowski, 2014; Seddigh & Stockholms Universitet, 2015).

To maintain connection, developing weekly virtual video calls for the team may help the need for face-to-face connection, but leaders should know it is not a complete replacement. The extent to which team members feel allied to each other and associated with the team’s vision and goals is the glue which keeps the team together. High-performing teams will have a strong connection, with everyone collaborating to achieve success.

Teams that already work together globally are going to have differing experiences based on what is happening in their given area. Patience, tolerance and care is the best operational leadership tactic one can use at this time. Give people the time to vent and share stories outside of the current tasks and day-to-day work. These open discussions will build team cohesion better than any other planned event one could facilitate.

Avolio, B. J., Sosik, J. J., Kahai, S. S., & Baker, B. (2014). E-leadership: Re-examining transformations in leadership source and transmission. The Leadership Quarterly, 25 (Leadership Quarterly 25th Anniversary Issue), 105-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.003 doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.003

Brown, R., Duck, J., & Jimmieson, N. (2014). E-mail in the workplace: The role of stress appraisals and normative response pressure in the relationship between e-mail stressors and employee strain. International Journal of Stress Management, 21(4), 325-347. doi:10.1037/a0037464

Guinalíu, M., & Jordán, P. (2016). Building trust in the leader of virtual work teams. Spanish Journal of Marketing-ESIC, 20(1), 58-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reimke.2016.01.003

Hoch, J., & Kozlowski, S. (2014). Leading virtual teams: Hierarchical leadership, structural supports, and shared team leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(3), 390-403. https://doi-org.lopes.idm.oclc.org/10.1037/a0030264

Jiang, L., & Probst, T. M. (2015). Do your employees (collectively) trust you? The importance of trust climate beyond individual trust. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 31(4), 526-535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2015.09.003

Johns, T., & Gratton, L. (2013). The third wave of virtual work. Harvard Business Review, 91(1), 66-73. ISSN 0017-8012

Judge, T. A., & Zapata, C. P. (2015). The person-situation debate revisited: Effect of situation strength and trait activation on the validity of the big five personality traits in predicting job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 58(4), 1149–1179.http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0837

Lockwood, J. (2015). Virtual team management: what is causing communication breakdown?. Language and Intercultural Communication, 15(1), 125-140. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2014.985310

Morgan, L., Paucar-Caceres, A., & Wright, G. (2014). Leading effective global virtual teams: The consequences of methods of communication. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 27(6), 607-624.

Petković, M., Orelj, A., & Lukić, J. (2014). Managing employees in a virtual enterprise. Singidunum Journal of Applied Sciences, 227-232. https://doi.org/10.15308/sinteza-2014-227-232

Politis, J. (2014). The effect of e-leadership on organisational trust and commitment of virtual teams. Proceedings of the European conference on management, leadership & governance, 254-261.

Short, H. H. (2014). A critical evaluation of the contribution of trust to effective technology enhanced learning in the workplace: A literature review. British Journal of Educational Technology, 45(6), 1014-1022. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12187

Seddigh, A. A., & Stockholms Universitet, S. O. (2015). Office type, performance and well-being: A study of how personality and work tasks interact with contemporary office environments and ways of working [eBook]. Stockholm: Department of Psychology, Stockholm University. Available from: SwePub, Ipswich, MA.